When I was an elementary school student growing up in southern California, one of the most amusing days in school was the first day of standardized testing. The amusement wasn’t directed at the test themselves, but at the consternation that the demographic questions caused our teachers. In California, at least, the standardized tests collected data on students with regard to our race and ethnicity. The format was the governmental standard, listing categories like “white, African-American, Asian, Native American,” followed by “Hispanic, non-Hispanic” and then a sub-list of countries that we could mark. The problems started immediately with my classmates who had immigrated from Armenia and Iran. Which category they asked, should they choose: White or Asian? Then my hand would shoot up, “Cambodia isn’t listed as a country. What should I do?” More questions would follow about whether Filipino/a students should check Hispanic or not, and as a class we would keep the questions going to try and delay the start of the test. The trials and tribulations of our elementary school teachers, point to an deeper underlying set of questions that AAPI Heritage Month raises: How do we define Asia? And why is Pacific Islander so often attached to the category Asian?

At face value, the answer to the first question, seems self-evident. “Asians” are people from the continent Asia. But how do we define the Asian continent? Most of us can agree that in the East, Asia ends at the Pacific Ocean. The traditional western boundary, the Caucasus Mountains, would include the people of countries like Iran and Afghanistan in Asia, which conforms neither to their own self-understanding, nor the way in which we use the term “Asian” in American English. This lack of fit between the self-understanding and geography points us to the fact that Asian, like so many of our categories, is culturally conditioned. In this post, I’ll explore a few different ways that people use “Asian” as a category, in the hopes of helping us see the broad diversity that we’re celebrating in this month.

Excursus: A Prehistory of “Asia”

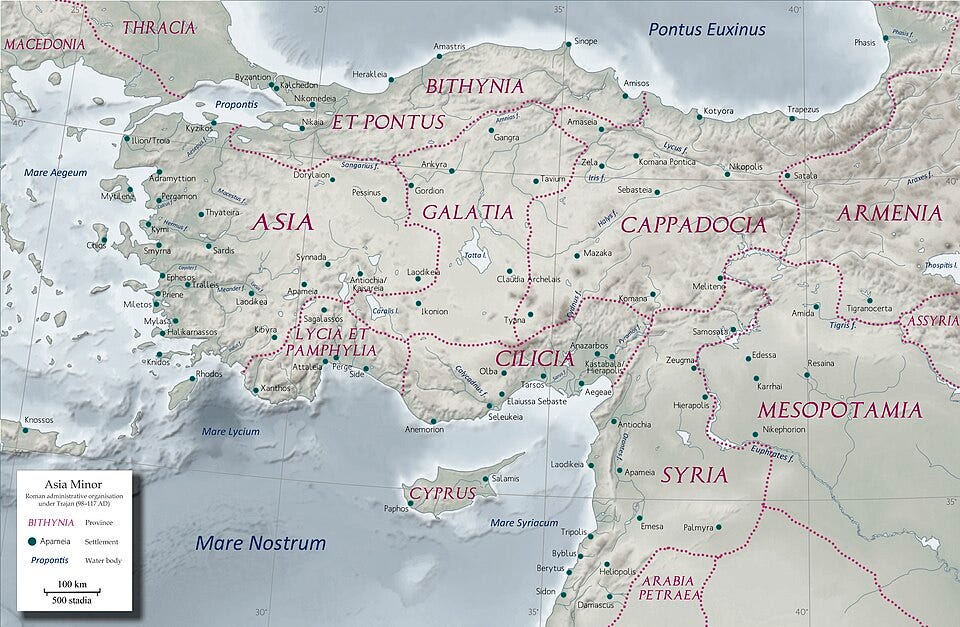

Just as a brief note, anytime that we talk about “Asian” in theological contexts, it’s useful as a point of contrast to begin with the occurences of the term Asia in the biblical text. Folks familiar with the travels of the Apostle Paul and the book of Revelation know that the use of the term Asia extends back into Roman times. The churches in Asia that John directs his revelations to (Rev 2-3) are in modern day Türkiye, and the Roman province was much farther west than we generally think of as “Asia,” in modern times. In modern discourse, we often refer to this province as “Asia Minor” to distinguish it from the continent Asia. So while some scholars like to claim that the New Testament has “Asian” origins (e.g. Scott Sunquist), it’s more a clever sleight of hand than an identification of the New Testament with the people who consider themselves Asian in the present day.

Asian at Home and Abroad

In contemporary discourse, Asia seems to begin where the “Middle East” ends (the ill-defined categories never end!). Thus, for most folks, Asia begins with Pakistan and then extends east. Interestingly, in British usage, Asian primarily refers to folks from Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. For example, I once sat next to a scholar from Australia at a conference on Asian American history. During the discussion, the scholar leaned over to me and asked if Americans counted Chinese and Koreans as “Asian.” I was taken aback by the question because in the United States, we tend to define Asian with reference to the “Far East,” i.e. China, Japan and Korea. When we talk about Asian manufacturing, for instance, we have those people in mind. All of this terminology gets at a fundamental problem: there is no one characteristic that binds all Asian people together. Rather, as we move across the Asia, we recognize that folks have cultural traits that they share with their neighbors. Even if the Chinese don’t have much in common with Indians, Indians and the Thai have a lot in common, and the Thai have much in common with the Vietnamese who have much in common with the Chinese. In other words, we have built our concept of Asian by linking together people groups in chains of cultural connection, not by identifying one thing that makes them all similar.

Extending the Chain

The concept of Asian as a chain that links people together explains in many ways why we celebrate Asian and Pacific Islander heritage together. For one, Asian cultures extend out onto islands in the Pacific Ocean: Japan, Taiwan, Indonesia and Malaysia are all “Pacific Islands.” Further, when we reach cultures like the Malay or the Filipino/as, we see that they have much in common with both mainland Asians and also with Pacific Islander cultures like the Polynesians. Partially this shared culture is a product of migration: places like the Philippines and Hawaii have large immigrant populations from China and Japan. It’s also a product of a long history of cultural exchange (and conflict) across the eastern Pacific. Celebrating AAPI Heritage month acknowledges that we cannot draw a sharp line between Asian and Pacific Islander cultures.

The Ends of the Chain

Now, you might be wondering: can’t we just continue linking cultures as described above? The answer, of course, is yes, and in the messy world of categories, our delineation may seem arbitrary. As we’ve already discussed, we tend to draw a line in the United States between “Middle East” and “South Asia.” To the east, geopolitical considerations seperate the Native people of the Americas from their counterparts across the Bering Strait, even though the indigenous people of Alaska and Canada have much in common with the people of the Amur River Basin in the Russian Far East. The Russians themselves have sometimes struggled over whether to consider themselves “European.” As yet another example of the blurry boundaries, when I lived in Norway, people often mistook my biracial facial features to mean that I was Sami (the indigenous people of Scandinavia).1

Finally, here in the United States, we see another struggle over Asian identity among people like myself who are biracial. While many of us who are half-Asian tend to be racialized and to consciously identify as Asian, the growing number of folks with a quarter or an eighth Asian heritage are doing the hard work of understanding what it means to be Asian when the links to “Asia” are in the distant past.

It can be quite overwhelming to try and grasp who constitutes Asia. And as biblical scholar Tat-siong Benny Liew noted, when it comes to scholarly questions like what is Asian American Theology or Asian American Biblical studies: “Some may question how one can decide whom to reference or cite if one is not even sure about ‘who’ and ‘what’ really counts as Asian American.”2 Dr. Liew goes on to answer by saying: “Don’t worry too much about it.”3 Such an answer is not meant to be flippant, but to recognize that reality that Asian has always been a constructed and contested category. As times and people change, we will continue to wrestle over what Asian means and who understands themselves as part of this category.

Thanks for coming along with me on this winding trip through different conceptions of Asia. On Friday we’ll be back with another alumni highlight! Please feel free to share this post with anybody you think might be interested and remember to subscribe if you’d like to keep receiving updates!

In the interests of accuracy, I should note that, like many Norwegians, I probably do have Sami ancestry several generations back on my father’s side, but it’s hard to say for sure because of the suppression of Sami identity in Norway in the 19th century.

Tat-siong Benny Liew, What is Asian-American Biblical Hermeneutics? Reading the New Testament, Intersections: Asian American Transcultural Studies (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2008), 7.

Liew, What is Asian-American Biblical Hermeneutics?, 8.

Can you post on the term “Oriental” I know it is out of use, but recently a friend said they had oriental food for dinner, I felt offended yet was unable to articulate to my friend why he should say Chinese over oriental. Or should he? Thanks